Who Is the False Prophet?

The Identity of the Second Beast of Revelation 13

With the little information we have about the second beast, we can come to a reasonable conclusion about its fulfillment. Because of the presence of the two horns, we can assume that the beasts of the sea and the earth rule together. Within this context, we must identify a candidate who shares his power with the papal Antichrist.

This beast is described as a deceptive fraud who looks like a lamb but speaks like Satan. He uses his lamb-like façade to fool Catholics into believing he is a servant of God while speaking blasphemously. The pope empowered the second beast to do a task he could not do himself: make people worship and revere him.

The False Prophet would also have the spiritual power to work incredible miracles. These unexplainable phenomena would drive many people closer to Catholicism, breathing life back into the Antichrist papacy at a time of weakness. However, the False Prophet’s power would not be solely spiritual. If anyone refused to worship the Antichrist, he would have the authority to put them to death.

The early Methodist reverend Joseph Benson saw the second beast as the corrupted clergy. The leaders of the medieval Catholic Church carried out the wicked, anti-Christian dictates of the papacy. Centuries later, during the Reformation, the medieval Catholic clergy evolved into a group of far more sadistic foot soldiers—the Society of Jesus, colloquially known as the Jesuits.

Once the Bible became more accessible to those outside the Catholic power structure, the men who would lead the Protestant Reformation could finally read and analyze God’s Word for themselves. The Reformers, many of whom were originally Catholics themselves, realized the Catholic identity of the Antichrist and Mystery Babylon and began to preach what they had discovered. They told people to listen to God’s warning in Revelation 18:4 and “come out of her”—and millions left Catholicism to become Christians.

Due to this schism, Ignatius of Loyola founded the Society of Jesus, or Jesuit Order, with the approval of Pope Paul III in 1540. According to the Jesuits, their founding mission was one of reconciliation. Today, the Jesuits claim that the objective of this reconciliation is “so that women and men can be reconciled with God, with themselves, with each other and with God’s creation.”[i] However, this is what every Catholic priest has always done. Why would Pope Paul III and Ignatius of Loyola need to create the Jesuits to do the same thing?

The Jesuits’ mission was not to reconcile men and women with God but to reconcile Protestants with Catholicism. Their goal was to combat the rapid spread of Protestantism in the early years of the Reformation using whatever means were necessary.

The Jesuits do not operate like pacifist priests. Instead, they behave like an intelligence agency, using clandestine fifth-column tactics to infiltrate and manipulate organizations from the inside. When an influence operation fails, the Jesuits often resort to violence. As Jesus cautioned during the Sermon on the Mount, “Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.”[1]

One example of Jesuit violence occurred after Protestant King James I expelled the Jesuits from England on February 22, 1604. The following year, on November 5, 1605, the Jesuits attempted the Gunpowder Plot, a failed effort to demolish the Parliament building and assassinate the King and his Protestant government. At the time, the Jesuits’ role in the conspiracy was so transparent that it was known as the “Jesuit Treason.”[ii]

The Society of Jesus has either been suspected or proven to be behind the assassinations of numerous heads of state and religious leaders. For their actions, the Jesuits have been expelled from dozens of countries since their inception. Portugal, France, Sicily, Malta, Parma, Spain, Austria, and Hungary expelled the Order in the second half of the eighteenth century.[iii] At least thirty-five significant and well-documented occurrences of Jesuit expulsion occurred between 1590 and 1990.[iv]

However, the number of Jesuit expulsions may be significantly higher. According to Jesuit priest Thomas J. Campbell, the Jesuits were banned from at least eighty-three countries, city-states, and cities between 1555 and 1931. In fact, the Order has been expelled from every European country at one time or another.[v] Virtually every expulsion was due to infiltration, political intrigue, subversion, or incitement to insurrection.[vi]

Partial list of significant expulsions of the Society of Jesus.[vii]

You will notice from the list of Jesuit expulsions that one stands out from the others. On July 21, 1773, Pope Clement XIV issued Dominus ac Redemptor, a papal brief that entirely dissolved the Jesuit Order. Upon signing the decree, the pope—knowing well the evil methods of the Jesuits—declared, “I have signed my death warrant.” Fourteen months later, he was proven correct. Before his death, a suffering Pope Clement said, “I knew that I would pay with my life for what I did; but I never anticipated such a long-drawn-out agony and such refinement of cruelty.”[viii]

Clement XIV was succeeded by Pius VI, the pope eventually deposed by Napoleon’s army in 1798. Pope Pius VI’s successor was a pope of the same name—Pius VII. In the first year of his pontificate, Pope Pius VII signed the Catholicae Fidei, which allowed the Jesuits to work in Russia. Several years later, in August of 1814, his Sollicitudo Omnium Ecclesiarum restored the Jesuit Order in full.[ix]

Even Pope John Paul I, who served as pope for only thirty-three days before his sudden death on September 29, 1978, was rumored to be a victim of Jesuit assassination. In his book The Jesuits: The Society of Jesus and the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church, Irish Catholic priest Malachi Martin detailed the Jesuits’ potential motive. John Paul I was scheduled to give a critical speech to the General Congregation of the Jesuits in Rome on September 30, 1978, the day after his premature death. Martin wrote, “One of the striking features of his speech was John Paul I’s repeated reference to doctrinal deviations on the part of Jesuits. ‘Let it not happen that the teachings and publications of Jesuits contain anything to cause confusion among the faithful.’ Doctrinal deviation was for him the most ominous symptom of Jesuit failure. Veiled beneath the polished veneer of its graceful romanità, that speech contained a clear threat: the Society would return to its proper and assigned role, or the pope would be forced to take action.”[x]

The leader of the Jesuit Order is the Jesuit superior general, who, like the pope, reigns for life. The superior general is so influential that many believe he is more powerful than the pope, even sharing twin nicknames based on their attire—the “white pope” and the “black pope.” These two men—one who operates in the sunlight, the other in the shadows—are the two religious leaders represented by the horns upon the head of the False Prophet beast of the earth.

Revelation 13:12, 15

12 And he exerciseth all the power of the first beast before him, and causeth the earth and them which dwell therein to worship the first beast, whose deadly wound was healed.

15 And he had power to give life unto the image of the beast, that the image of the beast should both speak, and cause that as many as would not worship the image of the beast should be killed.

Revelation 13:12 and 13:15 seem to describe the actions of the Catholic Church during the Great Tribulation, particularly after the Reformation and the convening of the Council of Trent in 1545. The council’s purpose was twofold: first, to find ways to bring the Protestants back to Catholicism and, more importantly, to protect the Roman Catholic Church and its papacy from being exposed as Mystery Babylon and the Antichrist.

The climax of church malice and tyranny occurred between the start of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 and the papacy’s loss of temporal power in 1798. The Jesuits pressured Catholic nations into wars against Protestant nations. Christians who would not worship or show reverence to the pope and his church endured humiliation, torture, floggings, and burnings at the stake. During the later part of the Great Tribulation, an extraordinary amount of violence was caused by the laughably-named Society of Jesus.

If the Catholic Church wanted to prove the early Protestant Reformers correct—if it was purposefully trying to demonstrate Catholicism was a false church and the papacy was the Antichrist—it was tremendously successful. The more the church used persecution and intimidation, the less Christian it appeared, and the more parishioners Catholicism lost to Protestantism.

The Vatican’s loss of temporal power made its war on Christianity more difficult. Rather than open and transparent persecutions, the Jesuits resorted to clandestine tactics—presenting themselves as benevolent priests focused on ministry, education, science, community service, and social issues while their true mission remained political influence and the defeat of Christianity.

The Jesuits’ methods were so effective that Adolf Hitler selected their Order as the model for the infamous Nazi SS squads. After World War II, the former chief of Nazi counter-espionage, Walter Schellenberg, confessed, “The SS organization had been built up by Himmler on the principles of the order of the Jesuits. The service statutes and spiritual exercises prescribed by Ignatius Loyola formed a pattern which Himmler assiduously tried to copy. Absolute obedience was the supreme rule; each and every order had to be accepted without question. The ‘Reichsfuehrer SS’—Himmler’s title as the supreme head of the SS—was intended to be the counterpart of the Jesuits’ ‘General of the Order,’ and the whole structure of the leadership was adopted from these studies of the hierarchic order of the Catholic Church.”[xi] The SS was the Nazi paramilitary organization most responsible for the Holocaust.

The Creation of Futurism and Preterism

The Protestant Reformers were nearly all Historicists. Before Preterism and Futurism existed, these Christian theologians taught Daniel’s seventieth week was right where it should be—immediately following the sixty-ninth. They recognized the Antichrist would originate from the same people who destroyed the Second Temple—the Romans. They warned Christians that Mystery Babylon—the worldwide false church headquartered in Rome—was the Catholic Church. They cautioned that the papacy was the Antichrist and the Great Tribulation was the period of papal persecution that began during the early Middle Ages and was still active in the sixteenth century. The Roman Catholic Church and its papacy, facing an existential crisis, needed to react.

The Historicist view of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks contains no gap and is easily interpreted.

Futurism

In 1590, a Jesuit priest named Francisco Ribera released a commentary on the Biblical end-times prophecies entitled In Sacrum Beati Ioannis Apostoli, and Evangelistiae Apocalypsin Commentarij (In the Sacred Book of Blessed John the Apostle and Commentary on the Gospel of the Apocalypse).[xii] The book, written solely to discredit Historicism and deflect attention from the Protestants’ criticisms of the Catholic Church, claimed that the prophetic chapters of Revelation would all be fulfilled sometime in the future.

According to Ribera, the apostasy Paul described in II Thessalonians 2 would be a falling away of the Catholic Church from the papacy rather than from God. After this papal apostasy, an Antichrist would confirm a covenant with Israel—a misinterpretation of Daniel 9:27, a verse that predicts Jesus’ death would fulfill the Davidic Covenant—and reign peacefully for three and a half years. After this time of calm, the Antichrist would violate his covenant, declare himself God inside a yet-to-be-built Third Temple in Jerusalem, and abolish all other religions. According to Ribera’s theories, the Antichrist will then persecute true Christians during a three-and-a-half-year Tribulation, and anyone who does not submit to a physical mark of the beast would be shut out of the global financial system.[xiii]

The eschatological interpretation Ribera produced is what scholars now call Futurism. Rome quickly adopted this viewpoint as the official position of the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, discerning Christians quickly identified this interpretation as a deliberate distortion of Biblical prophecy. The Vatican needed a new approach to persuade Protestants to abandon Historicism in favor of their Futurist ruse.

The Jesuits were unsuccessful for over two centuries, as the accuracy and simplicity of Historicism made it the only correct interpretation for those not under the manipulative thumb of Catholicism. Then, in 1811, the book The Coming of Messiah in Glory and Majesty was published. Written by Rabbi Juan Josafat Ben-Ezra—purportedly a Jew who had converted to Christianity—the book was another Futurist commentary on John’s Revelation. This time, however, the Protestants were far more receptive to the Futurist opinion. To them, the author being a non-Catholic Messianic Jew made his commentary more acceptable than one written by a Jesuit priest. But there was a problem. Rabbi Ben-Ezra did not write The Coming of Messiah in Glory and Majesty. In fact, he did not exist. Rabbi Juan Josafat Ben-Ezra was a pen name used to disguise the author’s identity; Manuel de Lacunza, a Spanish Jesuit priest.[xiv]

Lacunza’s work promptly gained credibility amongst Spanish speakers, particularly in Spain, Mexico, and South America. The Spanish Inquisition purposely banned the book in 1819, and Pope Leo XII placed it on the Index of Prohibited Books in 1824. Both acts were probably intended to enhance Protestants’ impression of it as an unapproved exposition that did not align with Roman Catholic teaching.

After the book’s publication in London, it was discovered by the Scottish reverend Edward Irving, who had a rudimentary understanding of Spanish. Irving was so enamored with Lacunza’s Futurist opinions that he translated the book into English, which he then released as a two-volume set in 1827.[xv] Before Irving’s translation, the Futurist view of Revelation was unknown to the Protestants of North America.[xvi] His English translation of The Coming of the Messiah in Majesty and Glory was the unfortunate catalyst that eventually led to the adoption of Futurism in most Protestant denominations.

Edward Irving was also the man most responsible for the anti-scriptural theory of a pre-Tribulation rapture—an idea with no basis in scripture.[xvii] This development also benefited the Catholic Church—if a rapture had to occur before the start of the Tribulation, the Catholic persecution of true Christians between 538 and 1798 could be easily excused as a long series of unfortunate incidents instead of the works of the Antichrist.

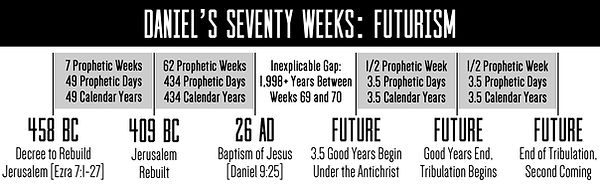

The Futurist eschatological interpretation is based on a misinterpretation of the final week of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks Prophecy. In Futurism, the first sixty-nine weeks align with the Historicist reading of the prophecy. However, after the sixty-ninth week, the Futurists change the focus of the prophecy from Jesus to the Antichrist. This misinterpretation inserts a two-millennium gap between the sixty-ninth and seventieth weeks, as the subscribers to this view claim the Antichrist has not yet emerged. Futurism also depends on an intentional misinterpretation of the phrase, “and the people of the prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary,” a reference to the actions of the destroyers of the Temple, not the actions of the Antichrist himself.

Futurist interpretation of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks Prophecy, with a gap of at least 1,998 years.

Preterism

The Jesuits of the Counter-Reformation were not comfortable relying on Futurism alone to confuse the Protestant converts and remaining Catholics. Luis del Alcázar, another Spanish Jesuit priest, wrote his own commentary on Revelation with vastly different views from the Futurists and Historicists. In his 1614 posthumously-published work entitled Vestigatio Arcani Sensus in Apocalypsi (A Trace of the Mysterious Meaning in the Apocalypse), Alcázar proposed that Revelation’s prophecies had been completely fulfilled in the first century. According to his theory, Daniel’s seventieth week occurred during the First Jewish-Roman War, from 66 to 73 AD.

Preterism is based on a dual translation of a single word in Jesus’ Olivet Discourse, delivered only days before the Last Supper. After teaching in the Temple, Jesus casually predicted the building would be demolished. Stunned, his disciples asked two separate questions. Of the Temple’s destruction, they questioned, “Tell us, when shall these things be?” Next, they asked, “And what shall be the sign of thy coming, and of the end of the world?”[2]

Jesus’ response simultaneously answered both questions, which makes for a challenging interpretation. Towards the end of his sermon, Jesus said, “This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”[3] The Greek word Jesus used for “generation” in Matthew 24:34, Mark 13:30, and Luke 21:32 is γενεά, or genea. Preterists latch onto this word to claim the end times should have occurred during the lives of the disciples. Because the Olivet Discourse occurred in 30 AD, the 70 AD destruction of the Second Temple certainly would have transpired during the lives of some of Jesus’ disciples, and therefore, within their generation as we define the word today.

However, the word γενεά had other meanings. Joseph Thayer’s A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament defines it as “that which has been begotten, men of the same stock, a family,” or “the several ranks in a natural descent, the successive members of a genealogy.”[xviii] These alternate definitions suggest the two meanings of Jesus’ prophecy interpreted γενεά differently. First, he predicted the destruction of the Temple would occur during the disciples’ generation, which it did. Second, he promised the lineage of Christians would continue through his second coming, never to be extinguished.

Preterism is the easiest eschatological interpretation to refute. It has far more versions and modifications than any other eschatological view. Various elements of the Biblical text must be twisted, distorted, or ignored to give the appearance of alignment with scripture. Similarly to Futurism, Preterism adds a subversive pause between the sixty-ninth and seventieth weeks in Daniel’s prophecy. Its sixty-ninth week ends in 26 AD, but its seventieth week does not start until 66 AD. Preterism also has no explanations for the seven seals, trumpets, and vials of Revelation other than to claim these events occurred in the spiritual world. For these reasons, Preterism was also rejected by the Protestants and only found acceptance within a desperate Catholic Church.[xix]

Most Preterists believe that Emperor Nero was the Antichrist and his persecution of Christians was the Great Tribulation. However, there is scant historical evidence of the Neronic persecution. Most of it comes from early church writers a century later, and there is no evidence that it lasted precisely three and a half years as they claim. If Nero did persecute Christians after the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, it likely only impacted Christians within the city and not across the empire. Other Preterists contend that the Temple’s destruction in 70 AD represents the Great Tribulation, despite it occurring two years after their alleged Antichrist’s death.

Like the Futurists, Preterists claim Daniel 9:27 predicted the Antichrist would confirm a covenant with many, but Nero never did. There is also no evidence that he restricted Christians from buying and selling. Nero’s 68 AD suicide, before the Preterists’ Great Tribulation occurred through either the Temple’s destruction or the conclusion of the Jewish-Roman War, invalidates his candidacy for the role of the Antichrist. No event occurred in 61 AD that might represent a starting point for a Neronian Antichrist’s final seven-year period of Daniel’s prophecy for the Preterists who base the seventieth week on the last seven years of Nero’s life. Nero also never “caused the sacrifice and the oblation to cease.” Most importantly, Jesus has not returned.

In one of many Preterist theories, the seventieth week occurs during the First Jewish-Roman War.

Another Preterist theory, which shows Nero’s persecution as the Tribulation.

This interpretation has so many flaws that the Preterists cannot agree on what to believe. Some believe Nero was the Antichrist, but the Tribulation was fulfilled by the First Jewish-Roman War. The war lasted seven years, but five of the seven years occurred after the death of their supposed Antichrist. Full Preterists believe the entirety of Revelation has been fulfilled, including the second coming of Jesus Christ. In their belief, Jesus returned in the spirit during the First Jewish-Roman War. If Christ returned in the first century, his living followers, including the gospel authors Luke and John, would have written about the event.

Many Preterists claim judgment day was a prophecy fulfilled by the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD rather than God’s judgment against the entire world. Some claim judgment day is ongoing even today, and others double down on their misinformed views and declare that we are currently living in the era of the new Heaven and new Earth described at the end of Revelation.[4]

A major problem with the Preterists’ interpretation is that their theories apply all end-times prophecies to the Jews of Judea. However, John’s first sentence in Revelation, “The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave unto him, to shew unto his servants things which must shortly come to pass,” proves the book was intended to warn Christians, not Jews.

When it was written, Revelation was a prophetic book, not a historical recollection of past events. For Preterism to be correct, Revelation had to be written before the start of the First Jewish-Roman War in 66 AD. However, nearly all non-Preterists agree that the book was written around 95 AD. Most of the earliest church writers believed John wrote his Apocalypse in the latter part of Domitian’s reign. At the end of the second century, Irenaeus wrote, “For at no long time ago was it seen, but almost in our generation, in the end of Domitian’s reign.”[xx] Irenaeus was a disciple of Polycarp, one of John’s disciples. In his book Salvation for the Rich, written around 203 AD, Clement of Alexandria wrote, “when after the death of the tyrant he removed from the island of Patmos to Ephesus.”[xxi] Clement’s reference to “the tyrant” dates John’s return from exile to just after the death of Domitian.

Victorinus of Pettau wrote his analysis of Revelation, Commentary on the Apocalypse of the Blessed John, shortly after 260 AD. “When John said these things he was in the island of Patmos, condemned to the labour of the mines by Caesar Domitian,” he asserted. “There, therefore, he saw the Apocalypse; and when grown old, he thought that he should at length receive his quittance by suffering, Domitian being killed, all his judgments were discharged. And John being dismissed from the mines, thus subsequently delivered the same Apocalypse which he had received from God.”[xxii] Other early church writers, including Jerome and Eusebius, supported the later 90-96 AD date for the book of Revelation.

Importantly, if Revelation was written after the beginning of the First Jewish-Roman War, the Preterists’ views are invalidated. To circumvent this substantial inconvenience, Preterists claim John wrote Revelation in 65 AD without any supporting evidence. Unfortunately for Preterism, the emperor at that time was Nero, who did not exile Christians.

Partial Preterist interpretation of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks (using the theory around the

First Jewish-Roman War as an example), with a future second coming.

Preterism is so inconsistent that yet another version of the interpretation exists. “Partial Preterism” takes most of the same positions as Full Preterism, but stops short of alleging Jesus has already returned. These Preterists believe the prophecies of Revelation 4-18 were fulfilled in the first century, but Jesus will return sometime in the future. This view still suffers from most of the same errors plaguing Full Preterism, including the distortion of the Seventy Weeks Prophecy. The only issue Partial Preterism attempts to resolve is Jesus’ missing second coming.

The seventeenth-century Dutch humanist and amateur theologian Hugo Grotius was the first prominent Protestant to adopt Preterism. Shortly after he told the Jesuit Denis Pétau he believed the Reformation was unwarranted, Grotius anonymously published a Preterist work called Commentary on Certain Texts Which Deal with Antichrist in 1640. However, Grotius also had to make his own changes to Preterism because of the interpretation’s many errors. He applied the seven seals to the time between Jesus’ life and the Jewish-Roman War, which predated John’s Revelation. He hypothesized that the 1,260-day prophecy of two witnesses in Revelation 11 was fulfilled when the Temple of Jupiter was built in Jerusalem, despite the relative unimportance of this event in Christian history. Curiously, he assigned the mark of the beast to the Roman emperor Trajan but attributed the Great Tribulation to Domitian’s Christian persecution—both of whom ruled after the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

After the true authorship of Grotius’ absurd commentary was exposed, he dropped all pretenses and enthusiastically worked to reunify Protestantism with Catholicism—a goal that aligned his objectives with Rome’s. Grotius was so eager to reunite Christianity and Catholicism that his concessions to Rome caused many to accuse him of converting to Catholicism. Eventually, the man who once authored his Preterist commentary anonymously openly advised Protestants to return to Roman Catholicism.[xxiii]

Nineteenth-century Biblical scholar Moses Stuart noted that the Preterist view espoused by Luis del Alcázar was advantageous to Rome as it freed the Catholic Church from the villainous role it plays in Revelation.[xxiv] The same observation can be made not only for Alcázar, but the Jesuit priests Francisco Ribera, Manuel de Lacunza, and Denis Pétau, each of whom helped to create or advance Futurism and Preterism to obscure the Historicist interpretation and shroud the Roman Catholic fulfillment of Mystery Babylon.

The process by which the early Protestants’ understanding of Revelation was clouded by the false interpretations of Futurism and Preterism shows all the signs of a Jesuit infiltration manipulating Protestantism from the inside. Once these two false interpretations gained a foothold within Protestantism, the Jesuit superior general and his priests pushed further. Due to centuries of effective covert tactics by the Jesuits, nearly all Christian denominations teach Futurism in their churches and seminaries today.

Solar emblems of the ancient Babylonian sun god Shamash[xxv] (left) and the Catholic Jesuit Order.

Summary

Interpretation of the Second Beast

-

Corrupt clergy, especially the Jesuits and the Jesuit superior general

-

Two horns represent the pope and the Jesuit superior general

-

The pope created the Jesuits in 1540 when the church structure was more stable and the papacy was threatened by Historicism

Mark of the Beast

-

The Antichrist’s followers would be sealed on the right hand or forehead

-

The mark is a contrast to God’s seal in Revelation 7

-

This mark is symbolic, not physical

-

-

Both the Greek and Hebrew words for “Romans” equal 666

-

The interpretation of 666 is irrelevant to who the Antichrist is

-

Futurism and Preterism

-

The Protestant Reformers studied the end times and were Historicists

-

The Jesuits were responsible for creating and popularizing both Futurism and Preterism to distract from the Reformers’ Historicist interpretation

-

Most Protestant churches teach Futurism today due to the influence and infiltration of the Jesuit Order

[1] Matthew 7:15 Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

[2] Matthew 24:1-3 1 And Jesus went out, and departed from the temple: and his disciples came to him for to shew him the buildings of the temple. 2 And Jesus said unto them, See ye not all these things? verily I say unto you, There shall not be left here one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down. 3 And as he sat upon the mount of Olives, the disciples came unto him privately, saying, Tell us, when shall these things be? and what shall be the sign of thy coming, and of the end of the world?

[3] Matthew 24:34 Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.

[4] Revelation 20:12 And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God; and the books were opened: and another book was opened, which is the book of life: and the dead were judged out of those things which were written in the books, according to their works.

Revelation 21:1 And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea.

[i] General Curia of the Society of Jesus. 2023. The Jesuits. August 7. Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.jesuits.global/about-us/the-jesuits/.

[ii] Fraser, Antonia. 1996. Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith In 1605. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

[iii] Maryks, Robert A., and Jonathan Wright (ed.). 2014. Jesuit Survival and Restoration: A Global History, 1773-1900. Leiden: Brill.

[iv] Roehner, Bertrand M. 1997. “Jesuits and the State: A Comparative Study of their Expulsions (1590-1990).” In Religion, 27:2 165-182.

[v] Funk & Wagnalls. 1983. “Jesuits.” In Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia, Vol. 15, edited by Leon L Bram, Robert S Phillips and Norma H Dickey, 36. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

[vi] Shepherd, J.E.C. 1987. The Babington Plot: Jesuit Intrigue in Elizabethan England. Springfield, OH: Wittenberg Publications.

[vii] Roehner, Bertrand M. 1997. “Jesuits and the State: A Comparative Study of their Expulsions (1590-1990).” In Religion, 27:2 165-182.

[viii] Pirie, Valerie. 1965. “Clement XIV.” In The Triple Crown: An Account Of The Papal Conclaves From The Fifteenth Century To Modern Times, 267-275. London: Spring Books.

[ix] Cross, Frank Leslie, and Elizabeth A. Livingstone. 2005. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 366. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[x] Martin, Malachi. 1987. “Papal Objections.” In The Jesuits: The Society Of Jesus And The Betrayal Of The Roman Catholic Church, 44. New York: Simon & Schuster.

[xi] Schellenberg, Walter. 1958. Hitler’s Secret Service (The Labyrinth), translated by Louis Hagen, 31-32. New York: Pyramid Books.

[xii] Brady, David. 1983. “The Contribution of British Writers Between 1560 and 1830 to the Interpretation of Revelation 13.16-18: (the Number of the Beast).” In Beiträge zur Geschichte der Biblischen Exegese 27: 202.

[xiii] Ribera, Francisco. 1590. Sacrum Beati Ioannis Apostoli, & Evangelistiae Apocalypsin Commentarij. Antwerp: Martin Nutius.

[xiv] Froom, Leroy E. 1950. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers, Vol. III, 303-324. Washington: Review and Herald Press.

[xv] Wilks, Washington. 1854. Edward Irving, an Ecclesiastical and Literary Biography, 273. London: William Freeman.

[xvi] Froom, Leroy E. 1950. The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers, Vol. III, 257. Washington: Review and Herald Press.

[xvii] Miller, Edward. 1878. The History and Doctrines of Irvingism, Vol. II, 8. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co.

[xviii] Thayer, Joseph Henry. 1889. “γενεά.” In A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, by Joseph Henry Thayer, 112. New York, Cincinnati, Chicago: American Book Company.

[xix] Cressener, Drue. 1689. “Preface.” In The Judgments of God Upon The Roman Catholic Church. London: Richard Chiswell.

[xx] Irenaeus. 1872. “Book V, Chapter XXX, Section 3.” In Five Books of S. Irenaeus Bishop of Lyons Against Heresies, translated by John Keble, 521. Oxford: James Parker and Co.

[xxi] Clement of Alexandria. 1919. “The Rich Man’s Salvation.” In Clement of Alexandria, translated by G. W. Butterworth, 357. London: William Heinemann.

[xxii] Victorinus. 1926. “Commentary on the Apocalypse, Chpater X, Section 11.” In The Anti-Nicene Fathers, Vol. VII, by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, 353. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons.

[xxiii] Froom, Leroy E. 1948. “V. Grotius—First Protestant to Adopt Alcazar’s Preterism.” In The Prophetic Faith of Our Fathers, Vol. II, 521-524. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Press.

[xxiv] Stuart, Moses. 1845. A Commentary on The Apocalypse, 464. Andover, MA: Allen, Morrill and Wardwell.

[xxv] Musée du Louvre. 2023. Stèle. October 31. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010174435.